Have any profs ever talked to you about testing?

There are a few “states of the art” for testing software:

Excel spreadsheet full of instructions to follow by hand

I am not making this up

Unit tests

Integration tests

Fuzz tests

For today, I want to talk about unit tests and their more interesting descendants.

Shamelessly borrowing from Wikipedia:

public class TestAdder {

public void testSum() {

Adder adder = new AdderImpl();

assert(adder.add(1, 1) == 2);

assert(adder.add(1, 2) == 3);

assert(adder.add(2, 2) == 4);

assert(adder.add(0, 0) == 0);

assert(adder.add(-1, -2) == -3);

assert(adder.add(-1, 1) == 0);

assert(adder.add(1234, 988) == 2222);

}

}Count the number of test cases below.

public class TestAdder {

public void testSum() {

Adder adder = new AdderImpl();

assert(adder.add(1, 1) == 2);

assert(adder.add(1, 2) == 3);

assert(adder.add(2, 2) == 4);

assert(adder.add(0, 0) == 0);

assert(adder.add(-1, -2) == -3);

assert(adder.add(-1, 1) == 0);

assert(adder.add(1234, 988) == 2222);

}

}Okay, don’t. It’s 7.

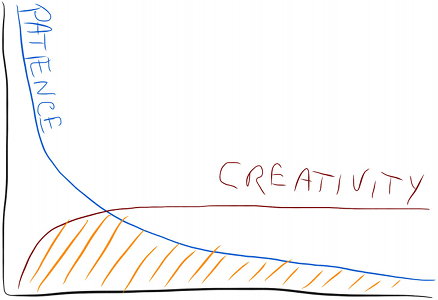

Unit tests are only useful up to a point.

Your patience and ability to think up nasty corner cases are VERY finite.

Best to use them wisely.

But how?

For patience, we have computers.

For nasty corner cases, we have random number generators.

Let’s put them to use.

UTF-16 is a Unicode encoding that:

takes a code point (a Unicode character)

turns it into 1 or 2 16-bit code units

Variable length encoding:

code points below 0x10000 are encoded as a single code unit

at and above 0x10000, two code units

We know that Char represents a Unicode code point.

The Word16 type represents a 16-bit value.

import Data.Word (Word16)What should the type signature of encodeChar be?

encodeChar :: ???We can easily turn the single-code-unit case into some Haskell using a few handy functions.

import Data.Char (ord)

ord :: Char -> Int

fromIntegral :: (Integral a, Num b) => a -> bWe use fromIntegral to convert from Int to Word16 because Haskell will not explicitly coerce for us.

encodeChar :: Char -> [Word16]

encodeChar x

| w < 0x10000 = [fromIntegral w]

where w = ord xTo encode code points above 0x10000, we need some new bit-banging functions.

import Data.Bits ((.&.), shiftR)The .&. operator gives us bitwise and, while shiftR is a right shift.

encodeChar :: Char -> [Word16]

encodeChar x

| w < 0x10000 = [fromIntegral w]

| otherwise = [fromIntegral a, fromIntegral b]

where w = ord x

a = ((w - 0x10000) `shiftR` 10) + 0xD800

b = (w .&. 0x3FF) + 0xDC00If you want unit tests, HUnit is the package you need.

import Test.HUnit (assertEqual)

testASCII =

assertEqual "ASCII encodes as one code unit"

1 (length (encodeChar 'a'))Let’s intentionally write a bogus test.

-- 𐆘

badTest = do

assertEqual "sestertius encodes as one code unit"

1 (length (encodeChar '\x10198'))If we run this in ghci:

ghci> badTest

*** Exception: HUnitFailure "sestertius encodes as one code unit\nexpected: 1\n but got: 2"Not pretty, but it works.

So I just slammed unit tests and now I’m showing you how to write them?

Well, we can generalize past the limits of unit tests.

What do we really want with this test?

testASCII = do

assertEqual "ASCII encodes as one code unit"

1 (length (encodeChar 'a'))We are really asserting that every ASCII code point encodes as a single code unit.

testOne char = do

assertEqual "ASCII encodes as one code unit"

1 (length (encodeChar char))What if we parameterize our test:

testOne char = do

assertEqual "ASCII encodes as one code unit"

1 (length (encodeChar char))And drive it from a harness:

testASCII = mapM_ testOne ['\0'..'\127']This is better, in that our original test is generalized.

It’s also worse, because we’re exhaustively enumerating every single test input.

We get away with it here because Unicode is small, and computers are fast.

But it’s the principle of the thing: automate better!

Forget about HUnit, here’s the package we’ll focus on.

import Test.QuickCheck

prop_encodeOne c = length (encodeChar c) == 1In ghci:

ghci> quickCheck prop_encodeOne

+++ OK, passed 100 tests.Why did quickCheck say this:

+++ OK, passed 100 tests.It did the following:

generated 100 random values for us

fed each one to prop_encodeOne

ensured that each test passed

Let’s look back at our “test function”:

prop_encodeOne c = length (encodeChar c) == 1This is very suspicious.

We know that encodeChar sometimes produces lists of length 2.

So why did our 100 tests pass?

For most types, QuickCheck operates from the handy assumption that “small” test cases are more useful than big ones.

As tests pass for small random inputs, it generates “bigger” ones.

With just 100 tests, we are simply not likely to generate a code point that encodes as two code units.

How does QuickCheck do its thing, anyway?

It needs to be able to generate random values.

This it achieves via typeclasses.

-- Generator type.

data Gen a

-- The set of types for which we

-- can produce random values.

class Arbitrary a where

arbitrary :: Gen a-- Generate a random value within a range.

choose :: Random a => (a,a) -> Gen a

instance Arbitrary Bool where

arbitrary = choose (False,True)

instance Arbitrary Char {- ... -}-- Simply protection for a Gen.

data Property = MkProperty (Gen a)

-- The set of types that can be tested.

class Testable prop

-- The instance bodies are not interesting.

instance Testable Bool

instance (Arbitrary a, Show a, Testable prop)

=> Testable (a -> prop)The two instances above are crucial.

Let’s write our test function with a type signature.

prop_encodeOne :: Char -> Bool

prop_encodeOne c = length (encodeChar c) == 1And quickCheck:

quickCheck :: Testable prop => prop -> IO ()If quickCheck accepts prop_encodeOne, then the latter must be an instance of Testable.

prop_encodeOne :: Char -> Bool

quickCheck :: Testable prop => prop -> IO ()But how? Via these two instances.

-- Satisfied by the result type

instance Testable Bool

-- Satisfied by the argument and result

instance (Arbitrary a, Show a, Testable prop)

=> Testable (a -> prop)If we pass quickCheck a function, then:

provided its arguments are all instances of Arbitrary and Show

and provided its result is an instance of Testable

then quickCheck can:

generate arbitrary values of all necessary types automatically,

run our test on those values,

and ensure that our test always passes

We still have a broken test!

quickCheck tells us that it always passes—when it shouldn’t!

Why? We have to read the source.

module Test.QuickCheck.Arbitrary where

instance Arbitrary Char where

arbitrary = chr `fmap` oneof [choose (0,127),

choose (0,255)]Oh great, QuickCheck will only generate 8-bit characters.

Our assumption that it would eventually generate big-enough inputs was wrong for Char.

Therefore our test can never fail.

How…unfortunate!

So now we face a challenge.

We want a type that is almost exactly like Char, but that has a different Arbitrary instance.

To create such a type, we use the newtype keyword.

newtype BigChar = Big Char

deriving (Eq, Show)The type is named BigChar; its constructor is named Big.

We use deriving to reuse the Eq instance of the underlying Char type, and to generate a new Show instance.

We want to be able to flesh this out:

instance Arbitrary BigChar where

arbitrary = {- ... what? ... -}The highest Unicode code point is 0x10FFFF.

We want to generate values in this range.

We saw this earlier:

-- Generate a random value within a range.

choose :: Random a => (a,a) -> Gen aIn order to use choose, we must make BigChar an instance of Random.

Here’s a verbose way to do it:

import Control.Arrow (first)

import System.Random

instance Random BigChar where

random = first Big `fmap` random

randomR (Big a,Big b) = first Big `fmap` randomR (a,b)If we want to avoid the boilerplate code from the previous slide, we can use a trick:

The GeneralizedNewtypeDeriving language extension

This lets GHC automatically derive some non-standard typeclass instances for us, e.g. Random

{-# LANGUAGE GeneralizedNewtypeDeriving #-}

import System.Random

newtype BigChar = Big Char

deriving (Eq, Show, Random)All we did was add Random to the deriving clause above.

As the name suggests, this only works with the newtype keyword.

An instance with a body:

instance Arbitrary BigChar where

arbitrary = choose (Big '\0',Big '\x10FFFF')A new test that unwraps a BigChar value:

prop_encodeOne3 (Big c) = length (encodeChar c) == 1And let’s try it:

ghci> quickCheck prop_encodeOne3

*** Failed! Falsifiable (after 1 test):

Big '\317537'Great! Not only did our broken test fail immediately…

…but it gave us a counterexample, an input on which our test function reproducibly fails!

The beauty here is several-fold:

We write a simple Haskell function that accepts some inputs and returns a Bool

QuickCheck generates random test cases for us, and tests our function

If a test case fails, it tells us what the inputs were

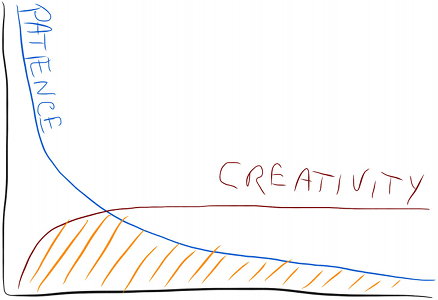

Unit test way:

QuickCheck way:

One property that you expect to hold universally true

Automatically, randomly generated test inputs

Counterexamples that help you pinpoint your bugs

There’s a problem with random inputs when a test fails:

They’re often big.

Big things are difficult for humans to deal with.

Big values usually take longer to look through.

Starting from a random failing input:

QuickCheck calls this shrinking.

Grab the following source file:

curl -O http://www.scs.stanford.edu/16wi-cs240h/ShrinkChar.hsUsing ghci to do some spelunking, work out a body for shrinkChar.

instance Arbitrary BigChar where

arbitrary = choose (Big '0',Big '\x10FFFF')

shrink (Big c) = map Big (shrinkChar c)

-- Write a body for this.

shrinkChar c = undefinedYou have 5 minutes.

Here are two different approaches to generating test values.

First, generate them directly (look at line 2):

prop_encodeOne2 = do

c <- choose ('\0', '\xFFFF')

return $ length (encodeChar c) == 1Second, generate any old value, but filter such that we get only the ones that make sense:

-- These two are basically the same, modulo verbosity.

prop_encodeOne4 (Big c) =

(c < '\x10000') ==> length (encodeChar c) == 1

prop_encodeOne5 = do

Big c <- arbitrary `suchThat` (< Big '\x10000')

return $ length (encodeChar c) == 1It is usually more efficient to generate only the values you’ll need, and do no filtering.

Sometimes, it’s easier to identify good values when you see them (by filtering) than to figure out how to generate them.

If QuickCheck has to generate too many values that fail a suchThat or other filter, it will give up and may not run as many tests as you want.

Grab the following source code:

curl -O http://www.scs.stanford.edu/16wi-cs240h/Utf16.hsWrite a definition for decodeUtf16:

decodeUtf16 :: [Word16] -> [Char]Decide on some (two?) QuickCheck tests, write them, and run them.

You have 10 minutes.

Test data generators have an implicit size parameter, hidden inside the Gen type.

QuickCheck starts by generating small test cases; it increases the size as testing progresses.

The meaning of “size” is specific to the needs of an Arbitrary instance.

Arbitrary instance for lists interprets it as “the maximum length of a list of arbitrary values”.We can find the current size using the sized function, and modify it locally using resize:

sized :: (Int -> Gen a) -> Gen a

resize :: Int -> Gen a -> Gen aWe’re hopefully by now familiar with the Functor class:

class Functor f where

fmap :: (a -> b) -> f a -> f bThis takes a pure function and “lifts” it into the functor f.

In general, “lifting” takes a concept and transforms it to work in a different (sometimes more general) setting.

For instance, we can define lifting of functions with the Monad class too:

liftM :: (Monad m) => (a -> b) -> m a -> m b

liftM f action = do

b <- action

return (f b)Notice the similarities between the type signatures:

fmap :: (Functor f) => (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

liftM :: (Monad m) => (a -> b) -> m a -> m bAll instances of Monad can possibly be instances of Functor. Ideally, they’d be defined in terms of each other:

class (Functor m) => Monad m where

{- blah blah -}For historical reasons, the two classes are separate, so we write separate instances for them and just reuse the code:

instance Monad MyThingy where

{- whatever -}

instance Functor MyThingy where

fmap = liftMIt turns out that lifting pure functions into monads is really common.

So common, in fact, that Control.Monad defines a bunch of extra combinators for us.

liftM2 :: (Monad m) => (a -> b -> c) -> m a -> m b -> m b

liftM2 f act1 act2 = do

a <- act1

b <- act2

return (f a b)These combinators go all the way up to liftM5.

Look familiar? Useful?

Before:

data Point a = Point a a

instance (Arbitrary a) => Arbitrary (Point a) where

arbitrary = do

x <- arbitrary

y <- arbitrary

return (Point x y)After:

import Control.Monad (liftM2)

instance (Arbitrary a) => Arbitrary (Point a) where

arbitrary = liftM2 Point arbitrary arbitraryQuickCheck provides us with machinery to shrink tuples.

Make use of this machinery to shrink a Point.

curl -O http://www.scs.stanford.edu/16wi-cs240h/TestPoint.hsTake 3 minutes.

import Control.Monad

import Test.QuickCheck

data Point a = Point a a

deriving (Eq, Show)

instance (Arbitrary a) => Arbitrary (Point a) where

arbitrary = liftM2 Point arbitrary arbitrary

-- TODO: provide a body for shrink

shrink = undefinedSuppose we have a tree type:

data Tree a = Node (Tree a) (Tree a)

| Leaf a

deriving (Show)Here’s an obvious Arbitrary instance:

instance (Arbitrary a) => Arbitrary (Tree a) where

arbitrary = oneof [

liftM Leaf arbitrary

, liftM2 Node arbitrary arbitrary

]The oneof combinator chooses a generator at random.

oneof :: [Gen a] -> Gen aPotential trouble:

This generator may not terminate at all!

It’s likely to produce huge trees.

We can use the sample function to generate and print some arbitrary data.

sample :: (Show a) => Gen a -> IO ()This helps us to explore what’s going on.

Here’s where the sizing mechanism comes to the rescue.

instance (Arbitrary a) => Arbitrary (Tree a) where

arbitrary = sized tree

tree :: (Arbitrary a) => Int -> Gen (Tree a)

tree 0 = liftM Leaf arbitrary

tree n = oneof [

liftM Leaf arbitrary

, liftM2 Node subtree subtree

]

where subtree = tree (n `div` 2)QuickCheck is pretty great. Take the time to learn to use it.

It’s a little harder to learn to use it well than unit tests, but it pays off big time.

Furthermore:

Enjoy!